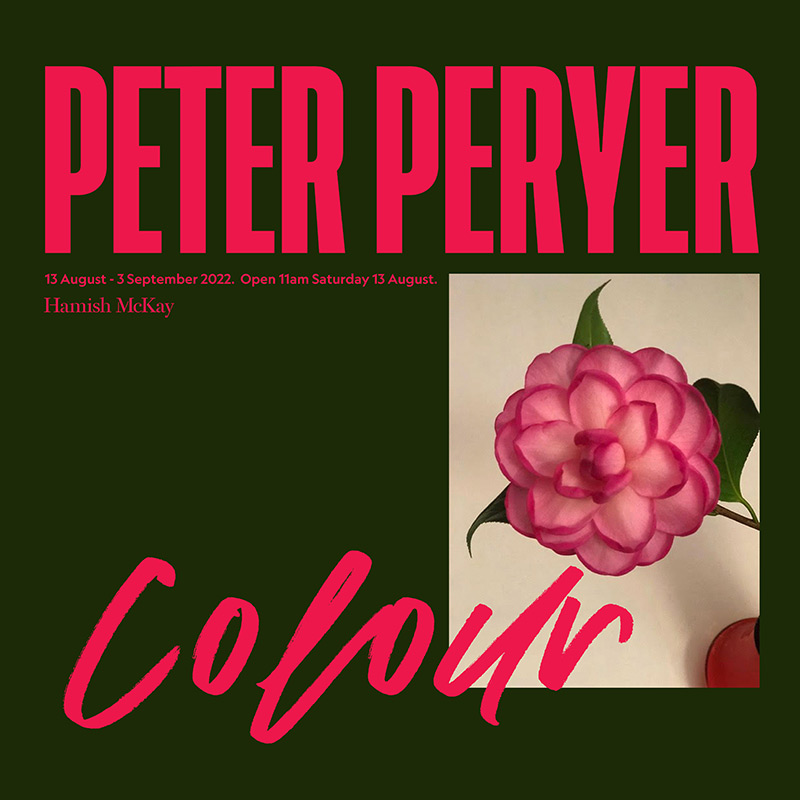

Peter Peryer – Colour

Invitation

Peter Peryer — Colour

Michael Moore-Jones

Peter Peryer was always attuned to what is these days called the vibe shift, those months and years when a culture rolls over. He stayed with the times, and stayed with his own vibe, later dismissing his own early work with epithets like the “moody blues… an easy way to get some impact into a photograph”, and saying he had moved in his photography from the “crucified Christ” to the “laughing Buddha.” Sometimes changing the vibe of his work sounded distinctly dangerous. Here he is in a 2014 interview, before an opening of a mini retrospective of his photographs: “It’s just what I need at this time in my career… A cup of meths on the barbie.”

Such was colour, for Peryer: a response to the vibe shift of the new millennium, a new possibility. Where Peter’s earliest works were charged with emotion and later works shifted to the more formal and geometric, colour seemed to help Peryer reconcile the two—and add a newfound laugh. The works shown here at Hamish McKay Gallery span Peryer’s early use of colour in the mid-2000s to his death in 2018, and show Peryer experimenting with varying quantities of those metaphorical spirits.

When he turned to colour Peryer was in his sixties and had spent almost three decades photographing in black and white, decades during which photography in New Zealand had struggled for recognition as art. If that had changed by the new millennium, colour photography—let alone that taken with a digital camera or an iPhone—still seemed to many to lack the gravitas some thought appropriate for a gallery. “It was a bit difficult for a while,” Peryer explained to filmmaker Shirley Horrocks, “because a lot of people who followed my work didn’t like me working in colour because they had the fundamental idea that somehow black and white is more ‘arty’…”

In that context you can almost feel the Peryer belly-laugh with an image like Newell, Oamaru, a “take that” with its faded florals, compressed ceiling, and even a gate to be latched across the staircase. No escape; bask in the wallpaper’s coloured glory! The attention to patterns and shapes is Peryer through and through, as is the sense of childhood memories long held at bay. On the other end of the spectrum, Scales seems to escape rigidity or a zombie-like formalism with the thin red line at the centre, suggesting a range of associations from tatau, to Fans, Fiji, or even the gash of red at the centre of McCahon’s Six Days in Nelson and Canterbury, a motif seen again in Carcass.

Peryer’s images of flowers might be his most difficult works, difficult for their banality and difficult for their popularity. Colour made these works possible, I think, letting Peryer see them in his own way, somehow more formalist than Edward Weston’s flowers and less sincere and romantic than Mapplethorpe’s. Peryer’s Rose, Camelia and Freesia retain the sense of casualness of a decisive moment (the corner of the vase in Camelia, the slight motion in Freesia) and yet could equally have involved the same months of forethought as in other images like Meccano Bus. That inability to decipher the nature of their making is their “Peryerness”. That, and the wink towards not just the long history of botanical photography, but the fact that that history itself had become cliche.

I am conscious I may be one of few viewers so far to have come to Peryer’s works for the first time once “Peryerland”, to use Peter Simpson’s term, was closed off after the artist’s death, rather than piecing that world together at the same time the photographer did. In that vein some have worried whether younger viewers will get the smile at the centre of Peryer’s photographs; whether millennials will see the depth in the images’ self-conscious superficiality. To this millennial, however, Peryer’s colour photographs are the way in, or through. People needn’t worry: Holy Tomato, Ice Cream, or Newell, Oamaru are like rosetta stones to Peryer’s world. They are proto-memes, say. In them you see the hearty laugh, and know that Peryer was this side of the millennium vibe shift.